Matot-Masei - Travelin' Prayer

Overcoming the "desert" of exile requires spiritual connection and prayer.

This week, we finish the book of Bamidbar and, as always, conclude by chanting "Chazak chazak v’nitchazek." This practice suggests that we can find strength in the ending of Bamidbar—an attribute we sorely need right now as we grapple with the terrible news from Israel about daily attacks on communities in the north by Hezbollah. Most recently, an attack on a Druze community resulted in the murder of 12 children and wounding of about 40 others. Once again, we find ourselves on the brink of war, and Israel’s situation remains as precarious as ever.

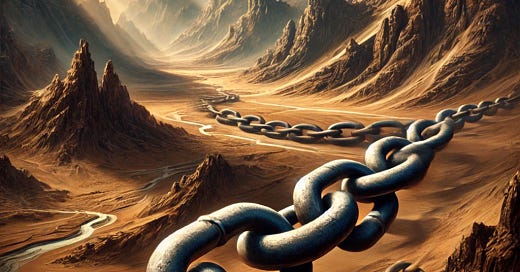

It's fitting, then, that this week’s double parsha is the final parsha of the book called Bamidbar, which means "in the desert"—an environment marked by instability and fraught with danger. It seems that the unpredictable desert locale was deliberately chosen for the process of apportioning rights to the land of Israel. The parallel between the journey through the desert and our own exile is inescapable: just as the Jewish people traveled through the desert, we travel through our exile with the same certainty that our ultimate destination will be Eretz Yisroel.

It is interesting to note that the word "bamidbar" has two distinct meanings. One translation is "in the desert." The other stems from a lightly different pronunciation "midaber," meaning "speaker." Both meanings of the word “bamidbar” are addressed in the two Torah portions we read today. Masei deals with the sojourn in the desert, and Matot begins with the laws about vows, which are a sacred form of speech.

Parshat Masei specifies every stopping point along our difficult journey through the desert. The Midrash explains that the purpose of recounting each of these stops is to remind us of all the different places where we’ve endured hardships with God by our side because those ordeals can often help us draw closer to Him. The same dynamic applies to our intimate relationships with other people—when we survive challenging experiences together, we often strengthen our bond with one another.

The focus of Parshat Matot is on the other meaning of Bamidbar; it discusses the laws of Nedarim (vows), which are a powerful form of speech. In addition to our awareness that lashon hara precipitated the destruction of the Beit Hamikdash, we are also reminded of this power during the High Holidays, when we annul our vows on Erev Rosh Hashana and again during Kol Nidre on Yom Kippur. Moreover, the voices of our prayers are a vital part of seeking success in the New Year. But how is the emphasis on Nedarim in Matot connected with the reminder in Masei that our precarious situation in the desert gave us the recurring opportunity to strengthen our bond with God? The connection lies in the essential nature of vows: they are not simply about words but about commitment in a relationship. That could be why the laws of nedarim are found not in Kodshim, the section of the Talmud that deals with holy objects, but rather in Nashim, the part that discusses marriage and divorce law.

The message of our double parsha during this period of the Three Weeks is that the entire Jewish people—those of us physically in galut and those who live in the land of Israel—are still in the “desert” of exile because we have not yet achieved peace and security. The way to emerge from the chaos and instability is through investing in, and strengthening, our personal relationships and our spiritual connection to God. We must take action, but we can only persevere in the face of uncertainty and fear if we deepen our relationship with God and seek His help by raising our voices in prayer.

Shabbat Shalom,

Eliezer Hirsch